This Month in Astronomical History: February 2021

Linda Shore Astronomical Society of the Pacific

Each month as part of this series from the AAS Historical Astronomy Division (HAD), an important discovery or memorable event in the history of astronomy will be highlighted. This month's author, Dr. Linda Shore, Chief Executive Officer of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, writes about the ASP’s creation and growth. Interested in writing a short (500-word) column? Instructions along with previous history columns are available on the HAD web page.

Each month as part of this series from the AAS Historical Astronomy Division (HAD), an important discovery or memorable event in the history of astronomy will be highlighted. This month's author, Dr. Linda Shore, Chief Executive Officer of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, writes about the ASP’s creation and growth. Interested in writing a short (500-word) column? Instructions along with previous history columns are available on the HAD web page.

Founding of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific

The Astronomical Society of the Pacific (ASP) was founded in San Francisco, California, on 7 February 1889.1 Astronomy had been practiced for millennia across the globe, but it wasn’t until the 19th century that astronomy became a profession that required a common language, principles defining best practices, and access to peer-reviewed research findings. During this era, many astronomical societies were established, some spearheaded by preeminent astronomers of the time.

The ASP was founded by Edward Holden, a former mathematics professor at the US Naval Academy and president of the University of California, who in 1888 had been appointed the first director of the university’s Lick Observatory.1 But the ASP’s origin is unique in that it traces its beginnings to a rare astronomical event and the hard work of a high school science teacher.1

On 1 January 1889, a total solar eclipse would be visible from several towns some 90 miles north of San Francisco.2 Just six months prior, Lick Observatory had been completed and made its first observations using its magnificent 36-inch refracting telescope, the largest of its kind in the world at the time.1 Edward Holden, eager to promote the new observatory, published a pamphlet on how to observe the upcoming eclipse.2 The pamphlet proved especially popular among amateur astronomers in California, including Oakland-based high school astronomy teacher Charles Burckhalter.1,3,4

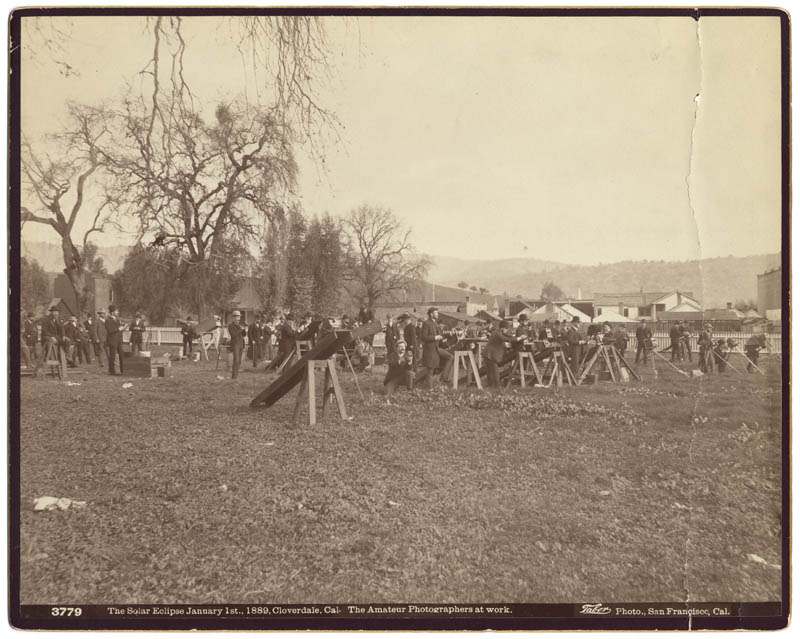

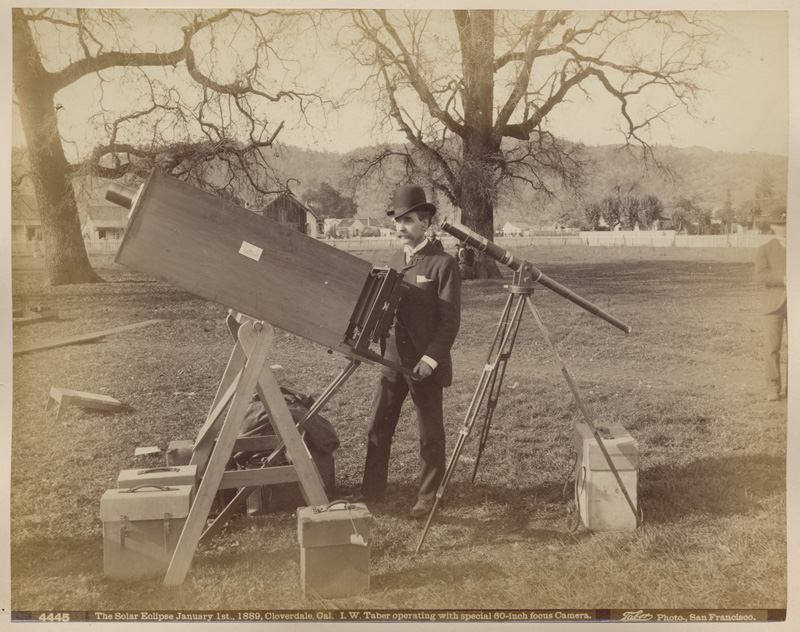

Burckhalter, who had been appointed the first director of Oakland’s Chabot Observatory in 1885, promoted photography — still in its formative stages — as a means to capture images of the eclipse.1,4 Using Holden’s publication as a guide, Burckhalter contacted the Pacific Coast Amateur Photographic Association (PCAPA) and organized an expedition for the purpose of imaging the eclipse and donating the plates to Lick Observatory.1,3,5,6 Sixty-five people made the trek north to Cloverdale, California, among them Burckhalter, 24 members of the PCAPA, and several women who hand-sketched the corona during the roughly two minutes of totality.1

The group of eclipse chasers met a month later at PCAPA’s San Francisco office in the heart of the city’s Barbary Coast district. On the evening of 7 February 1889, the group hosted a dinner, at which Edward Holden thanked the group for their contributions to astronomy. He also proposed the formation of a West-Coast astronomical society dedicated to continued collaboration between enthusiasts, amateurs, and professionals.1 The group formed the new society that very night — and the Astronomical Society of the Pacific was born.1

One hundred thirty-two years later, the ASP is an international organization dedicated to advancing understanding, promoting participation, and celebrating achievement in astronomy. The ASP’s mission — to increase public science literacy through astronomy and help make astronomy inclusive, diverse, and welcoming to all — echoes Holden’s original vision of a society open to anyone with a passion for astronomy, where “every class of talent and opportunity ought to find its profit.”5 Still headquartered in San Francisco, the ASP has become a center for the advancement of astronomy teaching and learning. Through its management of the NASA Night Sky Network, the society provides training and resources to over 400 amateur astronomy clubs across the country engaged in public outreach, and most recently has worked with clubs to make their interactions more inclusive and welcoming to young girls and underserved audiences.

The ASP has published storybooks for young children and their families designed to introduce the wonders of the night sky. The society’s many initiatives help science educators of all kinds present astronomy to a variety of audiences and include training and support for K-12 teachers, college astronomy instructors, amateur astronomers, museum educators, park rangers, scout leaders, librarians, and early career researchers interested in communicating science to the public.

In support of professional astronomers, the society continues to publish one of the world’s oldest and well-respected peer-reviewed journals, Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, and disseminates the proceedings of astronomy conferences worldwide through its ASP Conference Series.

The ASP also celebrates achievements in research and education through its many awards, such as the Bruce Gold Medal for lifetime achievement in astronomy and the Arthur B. C. Walker II Award recognizing leadership by an African American researcher to help diversify the scientific community. The inaugural recipient of the 2016 Walker award was NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson, whose groundbreaking career was highlighted in the motion picture Hidden Figures.

More information about ASP membership, publications, programs, initiatives, and awards — including ways to get involved — can be found at www.astrosociety.org.

Fig. 1. Amateur astronomers at work during the solar eclipse of 1 January 1889, in Cloverdale, California. (California State Library Picture Collection)

Fig. 2. Renowned photographer Isaiah West Taber operating a specially designed 60-inch-focus camera in a field in Cloverdale, California, 1 January 1889. (California State Library Picture Collection)

Fig. 3. Joint meeting of the American Astronomical Society and the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, Berkeley, California, August 1915. Seated in the first row of chairs, the "power row," are, from left to right, Robert G. Aitken, Richard H. Tucker, Edward A. Fath, Elizabeth B. Campbell, Frank Schlesinger (first Vice-President of the AAS), William Wallace Campbell, George Ellery Hale, and Armin O. Leuschner. The bald-headed man at the right, seated on the ground, is Joel Stebbins, later at various times Councilor, Secretary, Vice-President, and President of the AAS. Harlow Shapley, then at Mount Wilson, is in the back row, sixth from the left. (Mary Lea Shane Archives of the Lick Observatory, UC-Santa Cruz; identifications from Osterbrock, Donald E., "The First West Coast Meeting of the AAS," in DeVorkin, David H., ed., 1999. The American Astronomical Society's First Century, Washington, DC: American Astronomical Society, 37-39.)

Fig. 4. Middle- and high-school science teachers explore pinhole cameras during an ASP Summer Teacher Institute, 11 August 2017. (Brian Kruse, ASP photo archives)

Fig. 5. Katherine Johnson with the ASP's inaugural Arthur B. C. Walker II Award, 29 August 2016. (Linda Shore, ASP photo archives)

References

- Bracher, K. (1989). “The Stars for All: A Centennial History of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific,” Mercury, Sept/Oct 1989, 4-43.

- Holden, E. S. (1888). Suggestions for Observing the Total Eclipse of the Sun on January 1, 1889. Sacramento, CA: California State Printing Office.

- Aitken, R.G. (1923). “Charles Burckhalter, 1843-1923,” Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 35 (207), 252-254.

- Payne, W. W. (1889). “Total Solar Eclipse, Jan 1, 1889,” Sidereal Messenger, 8 (February 1, 1889), 64-68.

- Holden, E. S. (1889). “The Work of an Astronomical Society,” Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 1 (2), 9-20.

- Holden, E. S. (1894). “The Lick Observatory Eclipse Expeditions of January 1889, December 1889, and of April 1893,” Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 6 (38), 244-254.