This Month in Astronomical History

Teresa Wilson United States Naval Observatory

Each month as part of this series from the AAS Historical Astronomy Division, an important discovery or memorable event in the history of astronomy will be highlighted. This month, guest author Teresa Wilson of the Michigan Technological University focuses on Henrietta Swan Leavitt and the discovery of the relation between the luminosity and the period of Cepheid variable stars.

Each month as part of this series from the AAS Historical Astronomy Division, an important discovery or memorable event in the history of astronomy will be highlighted. This month, guest author Teresa Wilson of the Michigan Technological University focuses on Henrietta Swan Leavitt and the discovery of the relation between the luminosity and the period of Cepheid variable stars.

Henrietta Swan Leavitt

Women astronomers of the 20th century have garnered attention recently with the release of books and movies about their work and its importance for the advancement of science. In some cases, like that of the women computers of Dudley Observatory, not much is known. In others, like that of Henrietta Swan Leavitt, whose 150th birthday we celebrated on 4 July, their contributions have been acknowledged and celebrated, though perhaps insufficiently during their lifetimes.

Henrietta Swan Leavitt was born in 1868 to Congregational church minister George Roswell Leavitt and his wife Henrietta Swan Kendrick in Lancaster, MA. Following her public-school education in Cambridge, her family moved to Ohio, where she enrolled in Oberlin College in 1885. From 1988 to 1992 she attended the Harvard-affiliated Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women (later to become Radcliffe College).

An astronomy course at the Society had piqued her interest in the field, and she remained at Cambridge to volunteer as a research assistant at the Harvard College Observatory (HCO). After an intervening decade of travel, teaching school, and recovering from a serious illness which left her partially deaf, she returned to HCO.

In 1902, Harvard College Observatory director Edward Pickering invited Leavitt to join the permanent staff, which included Annie Jump Cannon, who was also deaf, and Williamina Fleming. Overall, Pickering hired about 80 women to do calculations and data analysis for approximately $0.25/hour. Leavitt worked on a project to catalog the position, color, and brightness of all the observable stars in the Milky Way, then thought by many to constitute the entire universe.

Leavitt was assigned to identify “variable stars”, stars whose brightness changes over time, using photographic plates. To do this, she would overlay two plates and note how their brightness changed between exposures. During this process, she discovered 1777 variable stars in the Magellanic Clouds, now known to be companion galaxies of the Milky Way. She published her results in 1908, noting that the brighter variables have longer periods. However, when she made her major breakthrough in 1912, Pickering published it under his own name. Using 25 of these stars, known as Cepheid variables for their similarity to δ Cephei, in the Small Magellanic Cloud, she determined that if two such stars have the same pulse rate, they also have the same intrinsic luminosity. Therefore, the one that appears dimmer must be farther away. Once calibrated, Leavitt’s period-luminosity relation, as it came to be called, allowed astronomers to estimate the distance to any Cepheid variable within reach of their telescopes.

Leavitt’s discovery was a turning point in how astronomers viewed the universe. Her work was the key to Harlow Shapley’s argument that the Sun lies in the outskirts, and not the center, of the Milky Way galaxy. It also allowed Edwin Hubble to declare with certainty that our galaxy was not the only one in the universe.

Shapley became the Harvard College Observatory director in 1921 and named Leavitt head of the stellar photometry department. Unfortunately, Leavitt died of cancer at the end of that year. Unaware of her death, Gösta Mittag-Leffler of the Swedish Academy of Sciences attempted to nominate her for the Nobel Prize for her discovery in 1924. Although she could not receive that prize, she did receive some post-humous recognition for her scientific contributions: an asteroid and a lunar crater both bear her name.

Photos:

- Henrietta Swan Leavitt. Taken before 1921. Photographer unknown. Public Domain.

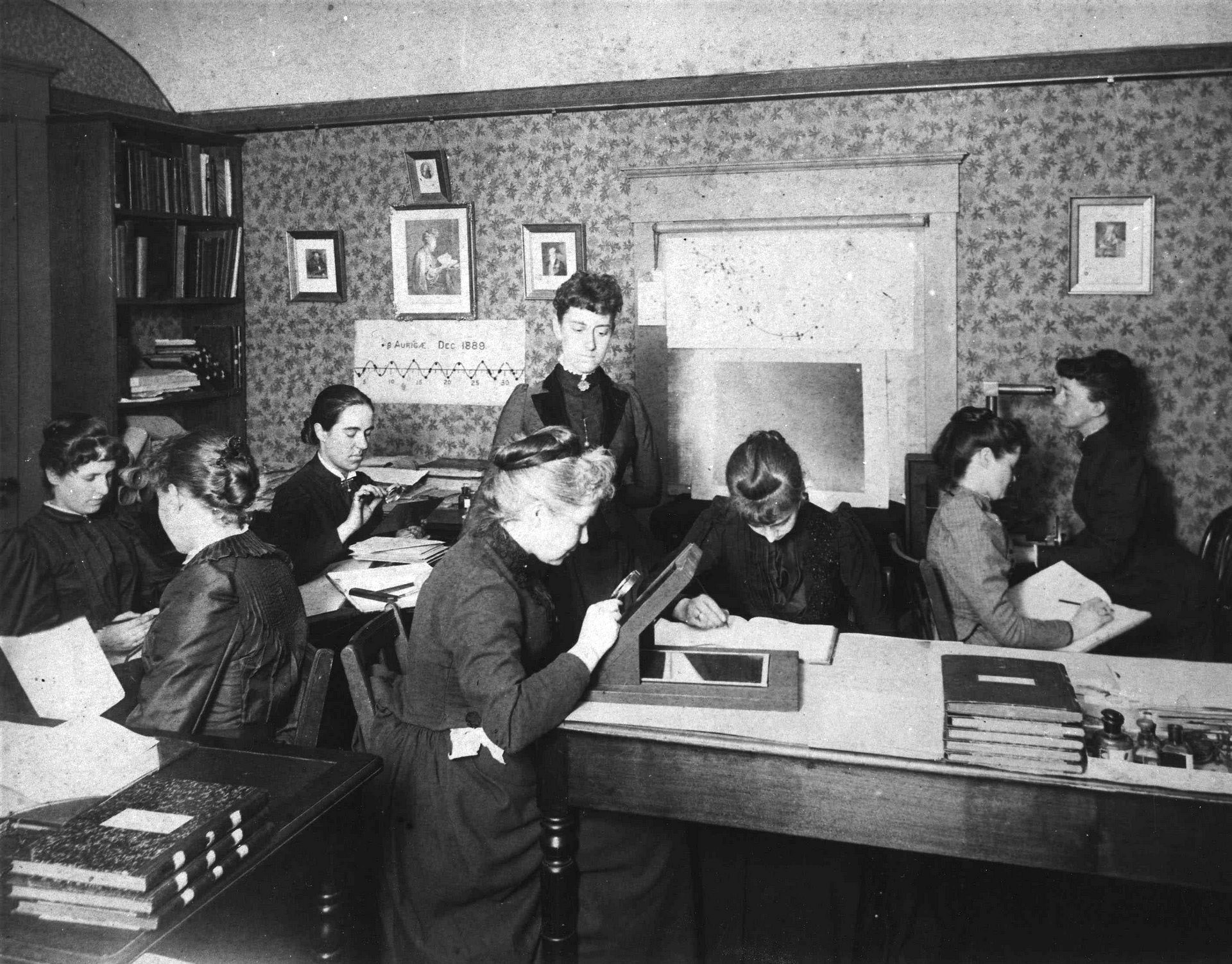

- "Pickering's Harem," so-called, for the group of women computers at the Harvard College Observatory, who worked for astronomer Edward Charles Pickering. The group included Henrietta Swan Leavitt seated, third from left, with magnifying glass, Annie Jump Cannon, Williamina Fleming standing, at center, and Antonia Maury. Taken circa 1890. Photo from the Harvard College Observatory. Public Domain.

Further reading:

1. Leavitt, H. S. 1908. "1777 Variables in the Magellanic Clouds," Annals of Harvard College Observatory 60: 4 (87–108)

2. Leavitt, H. S. & Pickering, E. C. 1912. "Periods of 25 Variable Stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud," Harvard College Observatory Circular 173 (1-3)

3. Sobel, D. 2016. The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars. Penguin.

4. Johnson, G. 2005. Miss Leavitt's Stars: The Untold Story of the Woman Who Discovered How to Measure the Universe. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

5. Gunderson, L. 2015. Silent sky. Dramatists Play Service.