This Month in Astronomical History: January 2022

Amy Oliver NRAO, ALMA

Each month as part of this series from the AAS Historical Astronomy Division (HAD), an important discovery or memorable event in the history of astronomy will be highlighted. This month's author, Amy C. Oliver, writes about William Herschel. Interested in writing a short (500-word) column? Instructions along with previous history columns are available on the HAD web page.

Each month as part of this series from the AAS Historical Astronomy Division (HAD), an important discovery or memorable event in the history of astronomy will be highlighted. This month's author, Amy C. Oliver, writes about William Herschel. Interested in writing a short (500-word) column? Instructions along with previous history columns are available on the HAD web page.

Strange Comet: William Herschel, His Telescopes, and Uranus

On 11 March 1787, Frederick William Herschel (1738-1822) identified two moons orbiting Uranus, first discovered on 13 March 1781. The moons were given the names Titania and Oberon.

Better known to us as an astronomer, Herschel was first an accomplished composer of 24 symphonies and 14 concertos. His astronomical work eclipsed his musical achievements. His accurate positional catalog of 2,500 deep-sky objects included the first resolution of individual stars within several nebulae. He is also credited with the first studies of infrared radiation from the Sun. In addition to Titania and Oberon around Uranus, he located two more moons orbiting Saturn, named Enceladus and Mimas.

Like so many other paradigm-shifting revelations, his finding of Uranus, the first planet not known in antiquity, was almost entirely by accident.

Herschel’s discovery of Uranus, however, did not start in the sky. Rather, it began on the ground, with the construction in 1778 of a 6.2-inch aperture 7-foot focal length (f/13.5) reflector telescope with 227x magnification, followed by a years-long methodical survey of the stars from his observatory in Bath.1 This same telescope would later go on to play a significant role in the development of Herschel’s catalog of double and multiple stars.

In the spring of 1781, William Herschel pointed his telescope toward the night sky and saw what he at first believed to be a new and somewhat unusual star in the constellation Gemini. Subsequent observations, however, revealed to Herschel that the nearby object could not be a star after all. Herschel presented his findings to the Royal Society on 26 April 1781, noting to fellow astronomers that, "...while I was observing the small stars in the neighborhood of H Geminorum, I perceived one that appeared visibly larger than the rest; being struck with its uncommon magnitude, I compared it to H Geminorum and the small star in the quartile between Auriga and Gemini, and finding it so much larger than either of them, suspected it to be a comet." 2

Despite his presentation to the Royal Society, Herschel remained uncertain whether his discovery was a comet or something else. After weeks of discussion, the astronomical community announced that Herschel had made the first discovery of a planet using a telescope, and more important at the time, the first discovery of a planet since antiquity.3 Herschel’s instant fame curried him favor with King George III — for whom Herschel had attempted to name the planet, Georgium Sidus — and after several demonstrations of his telescope’s excellence at the Royal Observatory and Windsor Castle, Herschel became the King’s private astronomer. The move, in turn, allowed Herschel to perfect his work as a professional astronomer and telescope maker, building and selling many small telescopes. He also completed his own instrument of 18.7-inch aperture and 20-foot focal length (f/12.83). Herschel even succeeded in constructing an f/10 40-foot telescope, though it proved not to be his favorite.4

Despite a busy new role for the palace, Herschel’s relationship with Uranus was far from over, and in 1787, he discovered two satellites orbiting the planet — Titania and Oberon. Herschel largely credited his discovery of the two moons to his decision to use not his favored and trusted 6-inch aperture and 7-foot focal length telescope built in 1785, but his new front-view construction that reflected light from the primary mirror directly to the eyepiece without the need for a secondary mirror. The arrangement made small objects, like stars (and in the case of Titania and Oberon, moons), appear brighter.5

Continued improvements to his telescopes and his science led to further discoveries and enhancements of astronomy, including the publication of his deep-sky objects catalog in 1786, the discovery of Enceladus and Mimas in 1789, and the discovery of infrared radiation in 1800.

Fig. 1: Herschel Telescope. William Herschel made this 7-foot Newtonian reflecting telescope with a 6.125-inch diameter mirror for his friend Sir William Watson between 1783 and 1785. Herschel ground and polished all of his own mirrors for his telescopes, including the original on which this telescope was based, the telescope he used to discover Uranus in 1781. This telescope is on permanent display at the Science Museum in Kensington, London. Credit: The Board of Trustees of the London Science Museum

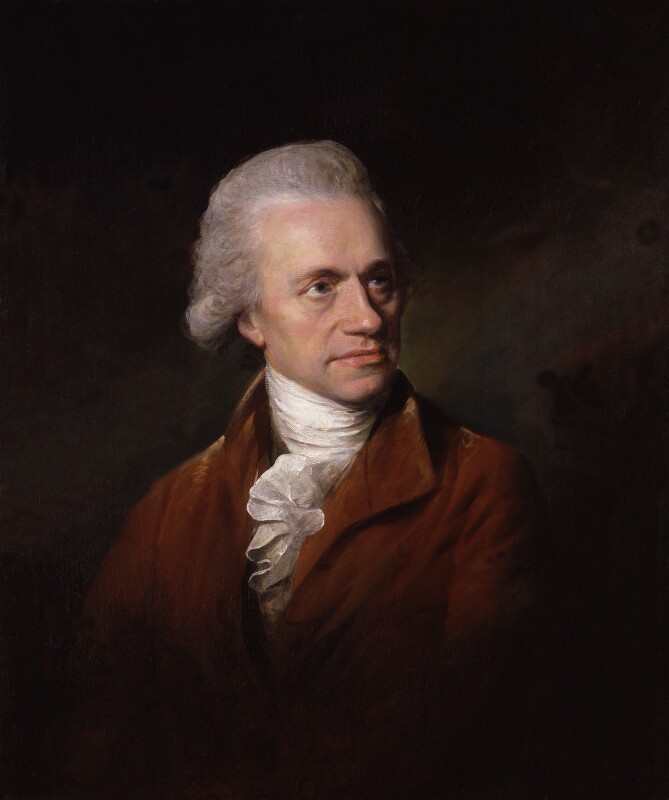

Fig. 2: Herschel (provided in a zip file with the license from the National Portrait Gallery). Sir William Herschel was a celebrated composer and astronomer who discovered Uranus in 1781, and two of its 27 known moons in 1787. Credit: Lemuel Francis Abbott, oil on canvas 1785, National Portrait Gallery NPG 98

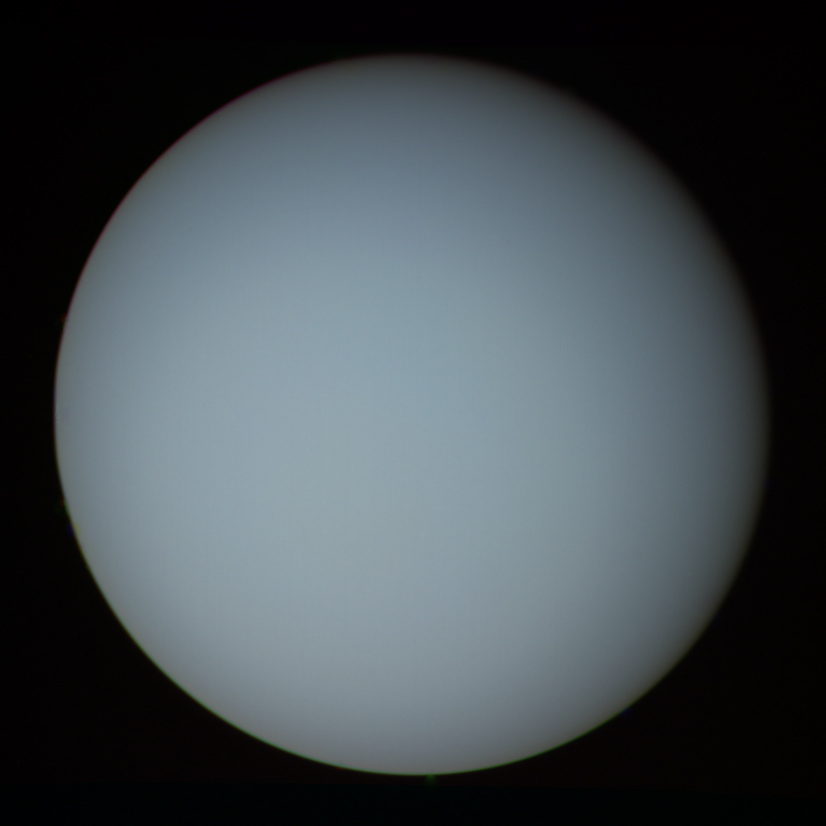

Fig. 3: Uranus. William Herschel discovered Uranus, the seventh planet, on 13 March 1781 while surveying constellation Gemini for double stars. This true-color image of Uranus was compiled from images returned from NASA’s Voyager 2 on January 17, 1986. Credit: NASA/JPL.

References

- Mullaney, J. (2007). The Herschel Objects and How to Observe Them. New York: Springer, pp. 15; An important distinction: The Herschel telescope used to discover Uranus in 1781 did not contain a 7-foot mirror despite the inference from the contemporary reports. Today’s astronomers measure telescopes by the diameter of their apertures. A second measure of focal ratio (focal length divided by aperture) has been adopted from photography.

- Herschel, W. (1781). "Account of a Comet," presented to the Royal Society on 26 April 1781.

- Prior to the discovery of Uranus, five planets were known to inhabit the night sky: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Knowledge of Uranus, and the observation of aberrations in its orbit around the Sun led to the confirmation of Neptune in 1846.

- Hoskin, M. (2003). "Herschel’s 40ft reflector: funding and functions," Journal for the History of Astronomy, Vol. 34, Part 1, No. 114, p. 1 - 32 (2003), Bibcode: 2003JHA....34....1H

- Cunningham, C., ed. (2018). The Scientific Legacy of William Herschel (Historical & Cultural Astronomy). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, pp. 190; Maurer, A. and Forbes, E.G. (1971). "William Herschel’s Astronomical Telescopes," Journal of the British Astronomical Association, Vol. 81, pp. 284-291, Bibcode: 1971JBAA...81..284M