This Month in Astronomical History: December 2021

Dan Broadbent Physical and Computer Sciences Librarian, Brigham Young University

Each month as part of this series from the AAS Historical Astronomy Division (HAD), an important discovery or memorable event in the history of astronomy will be highlighted. This month's author, Dan Broadbent, writes about the life work of Johannes Kepler. Interested in writing a short (500-word) column? Instructions along with previous history columns are available on the HAD web page.

Each month as part of this series from the AAS Historical Astronomy Division (HAD), an important discovery or memorable event in the history of astronomy will be highlighted. This month's author, Dan Broadbent, writes about the life work of Johannes Kepler. Interested in writing a short (500-word) column? Instructions along with previous history columns are available on the HAD web page.

The Order and Harmony of Johannes Kepler’s Work: Celebrating the 450th Anniversary of His Birth

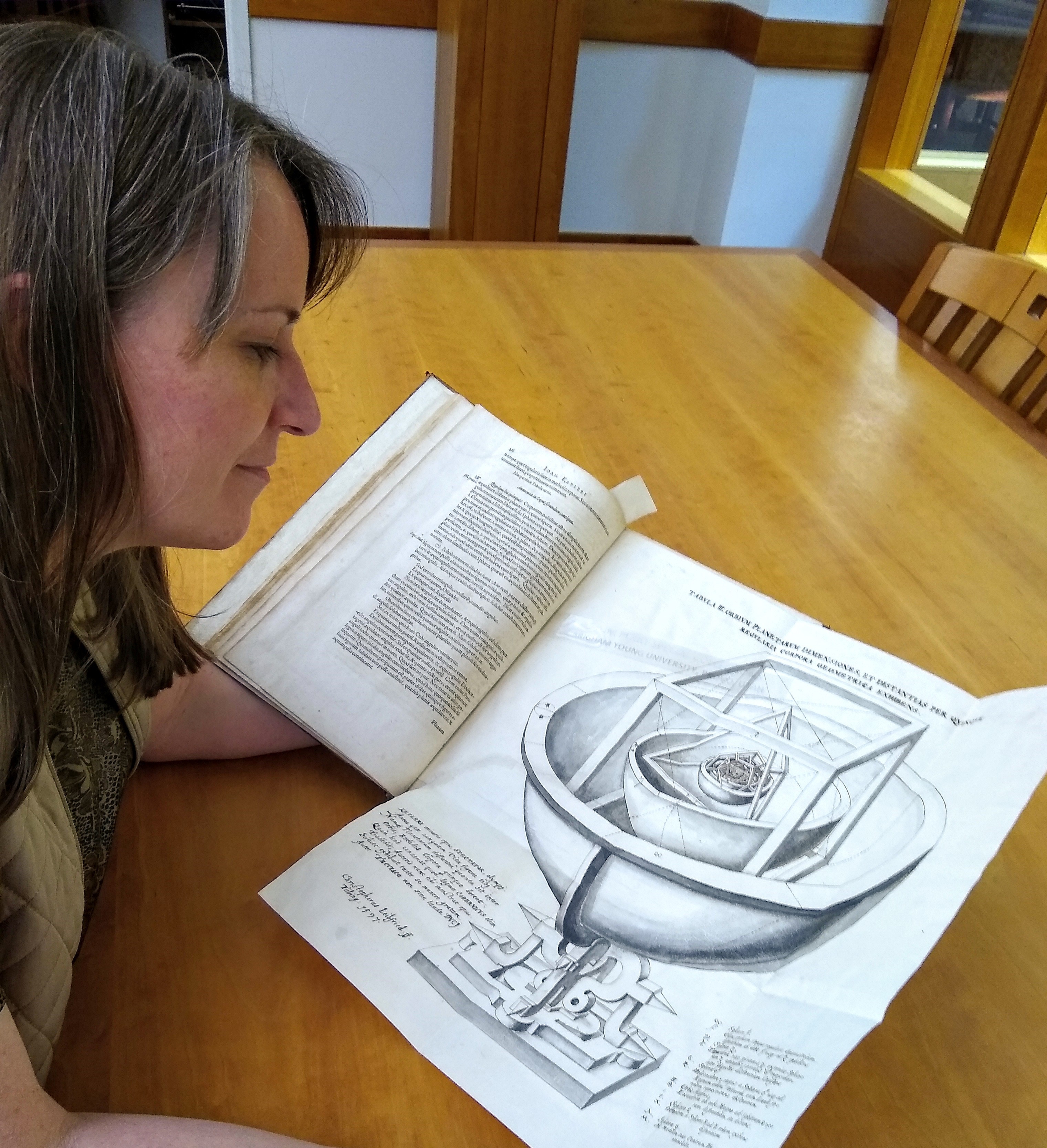

As the subject librarian for physics and astronomy at Brigham Young University, the author has had the privilege of handling some of Johannes Kepler’s original books preserved in the university’s archives. One of the most impressive materials in the archive is a large page from Mysterium Cosmographicum that unfolds to reveal a print of the Platonic solids, shown in Figure 1.

Kepler turned to the Platonic solids in his attempt to explain the orbits of the six then-known planets. While unsuccessful, the effort revealed how the concepts of order and harmony shaped Kepler’s view of the universe and influenced his explanations for his observations.

The concept of order describes a convenient or purposefully organized arrangement; harmony describes the consistency, congruity, or pleasing nature of that arrangement.

As Kepler observed the order and harmony of the planets' orbits, he connected that pattern with another orderly and harmonious pattern found in arranging the Platonic solids in just the right way. This correlation filled Kepler with delight, as he explained: "it will never be possible to describe with words the enjoyment which I have drawn from my discovery. Now I no longer bemoaned the lost time; I no longer became weary at work; I shunned no calculation no matter how difficult."1

For Kepler, order and harmony were not just patterns to be seen and appreciated. They were the foundation for how he observed and explained the universe around him. A compelling symmetry guided his efforts: if what was observed had order and harmony built into it, then the explanation for what was observed would be made, naturally, from the building blocks of order and harmony.

Kepler described the connection he felt from these building blocks: "whenever I consider in my thoughts the beautiful order, how one thing issues out of and is derived from another, then it is as though I had read a divine text, written into the world itself … saying: Man, stretch thy reason hither, so that thou mayest comprehend these things"2, and “the souls of human beings were formed in such a way that man expects harmonies as well as observes and grasps them.”3

It is important to note that order and harmony do not mean lack of change. In Kepler’s era, a supernova introduced what was thought to be a new star to the constellation of Cassiopeia. A comet also emerged and moved across the European sky. These events created difficulties for those who clung to Aristotle’s explanations that required the heavens to be perfect and unchanging. This was not a problem for Kepler, however, who was willing to consider various explanations.

The challenge for Kepler was that those explanations were “so far outside the bounds of previous thought that there was no evidence in existence for him to work with. He had to use analogies.”4 Those analogies were rooted in order and harmony. To explain why planets that are farther away from the Sun move slower than those that are closer, he considered parallels with other natural orders. Smells and heat dissipate with distance. Light diminishes with distance as well. Could planetary motion be linked to the sun’s light or heat? Magnetism also provided interesting possibilities; maybe the planets were like magnets. To explain why the planets all move in the same direction, Kepler drew from the effect a whirlpool’s swirling waters have on floating objects.5 Wherever a similar pattern or order existed, Kepler was willing to consider it.

Through his determination, natural brilliance, and utilization of order and harmony, Kepler made momentous discoveries. His three laws of planetary motion, still fully in use today, describe and predict exactly how planets move, not only in our solar system but anywhere in the universe. His work laid the foundation that Isaac Newton built on to develop the law of universal gravitation. Kepler improved the understanding of optics, including how vision occurs, and made advancements in geometry and mathematics. Order and harmony are at the root of science, and both are on generous display in the works and methods of Johannes Kepler.

Note: This article was adapted from the paper "Order and Harmony: Kepler's Guiding Forces" by the same author and included in the commemorative volume Towards Mysteries of the Cosmos with Johannes Kepler — on the 450th Anniversary of His Birth published by the Obserwatorium Atronommiczne Krolowej Jadwigi Rzepienniku Biskupim (Queen Jadwiga Observatory of Rzepiennik Biskupi Poland). Used with permission.

Fig. 1: Johannes Kepler: Mysterium Cosmographicum, Tübingen 1596, Tabula III: Orbium planetarum dimensiones, et distantias per quinque regularia corpora geometrica exhibens. Public domain. Courtesy, Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

References

- Caspar, M. (1959). Kepler. Abelard-Schuman, p. 63.

- Caspar, M. (1959). Kepler. Abelard-Schuman, p. 152.

- Kepler, J. (1858). In Frisch, C. (Ed.), Joannis kepleri astronomi opera omnia. Heyder & Zimmer, p. 228.

- Epstein, D. (2019). Range: Why generalists triumph in a specialized world. Penguin, p. 100.

- Epstein, D. (2019). Range: Why generalists triumph in a specialized world. Penguin

Suggested Further Reading

Koestler, A. (1959). The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe. Macmillan. Love, D. (2015). Kepler and the Universe. Prometheus Books.