Guest Blog: An Astronomer Learns to Make His CASE

Heather Bloemhard Vanderbilt University

This guest post is written by Kevin Cooke, a PhD candidate at Rochester Institute of Technology and the AAS sponsored participant for the 2016 AAAS Catalyzing Advocacy in Science and Engineering (CASE) Workshop.

— Heather Bloemhard, AAS Bahcall Fellow

From 17–20 April 2016, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) held a workshop titled Catalyzing Advocacy in Science and Engineering (CASE). This workshop invited 50 graduate and undergraduate students from various academic associations and universities. Each student had to be sponsored by one of these groups and I was fortunate enough to attend as a representative of the American Astronomical Society. The purpose was to expand our knowledge of how to best perform science advocacy as well as learn about the federal budget and advisory processes.

From 17–20 April 2016, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) held a workshop titled Catalyzing Advocacy in Science and Engineering (CASE). This workshop invited 50 graduate and undergraduate students from various academic associations and universities. Each student had to be sponsored by one of these groups and I was fortunate enough to attend as a representative of the American Astronomical Society. The purpose was to expand our knowledge of how to best perform science advocacy as well as learn about the federal budget and advisory processes.

One of the most striking qualities about the workshop was how the lessons and lectures they wrote were applicable to many disciplines. I was the only astrophysics graduate student in attendance, yet the group was filled with neuroscientists, biologists, chemists, and ecologists. Fields more applied to everyday life were feeling the same pressure that astronomers feel when justifying tax money expenditure.

Throughout the workshop, two points rose above all else. First is the saying, "There are three parties in Washington; Republicans, Democrats, and Appropriators." Whenever a budget must be passed for the future, the real control lies in the members of the relevant committees to which sections of the budget are delegated. Appropriators are split between the parties and often have their own unique relationships attached. The members of a given committee might have friendships and alliances which cross party lines due to their shared work on a given subject that they enjoy. It was an important lesson for us to not make a judgment that a given appropriator may blindly vote along a party line. Due to this, our arguments must be made in a proactive/positive tone. To advocate for the value of your own field is more effective in convincing the appropriators and their science advisors than suggesting the diminishment of another's budget to boost your own. Such negative behavior runs the risk of insulting a friendship between appropriators about which you may not know.

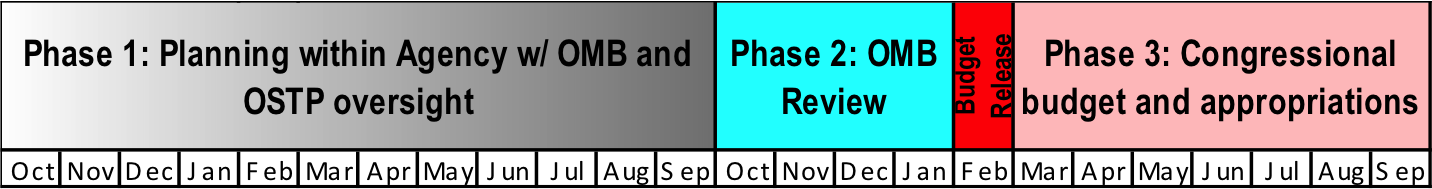

The second point was to know how the budget cycle works. Too many times, the science advisors of Congress members take meetings with advocates who argue fervently and passionately for a cause which has already had its committee make their decision. Another lesson regarding the budget cycle was that there are three budgets at work at any given time; the budgets for the current year, and the next two years (see the figure below). For example in April, the 2016 budget is being spent, the 2017 budget is working its way through Congress and appropriations, and the 2018 budget requests are already being internally planned by each government agency. Advocates look uninformed when they are out of sync with the budget cycle. However great the information might be, the advisors can't do anything with it because it's too early or too late. A good way to make sure your arguments for astronomy are heard and have an impact is to participate in a Congressional Visit Day hosted by the American Astronomical Society.

One of the largest activities during CASE was a mock reconciliation meeting in which groups of us were assigned parts in the Senate and House, and from Commerce, Justice, and Science backgrounds. We were given booklets of summaries of each of the different categories up for funding decisions, such as NASA's SLS rocket or the Justice Department's Federal Prison System. It's eye-opening to see how different departments are decided by the same committee, all while having to negotiate with the other party and landing close enough to the White House budget request that the budget can pass both the Executive and Legislative branches of the government.

The workshop ended with visits to the Senate and House offices. While the funding for our respective science fields had been decided already, we used the opportunity to discuss the AAAS and the growing interest of science policy in our graduate communities. We received a very warm welcome. Many of these advisors must serve in multiple capacities and juggle different subject matters. Developing a relationship with a constituent who has in-depth knowledge of a field and how it affects their home state or district makes the advisor's life easier while also enabling accurate science communication from our end.

In closing, the AAAS CASE Workshop is a great opportunity. Science advocacy is becoming stronger with time and more graduate students from all different fields are aware of how science advocacy can be possible in the post-PhD future. The AAAS now provides fellowships for recent graduates from whom Senators and Representatives request specialists, and there's been a noticeable shift towards acceptability among graduate advisors toward this career path. I recommend anyone interested in making sure astronomy has its voice to apply for sponsorship from the AAS or their home institution for next year's workshop.