This Month in Astronomical History: 100 Years for the Hooker Telescope

Teresa Wilson United States Naval Observatory

Each month as part of this new series from the Historical Astronomy Division of the AAS, an important discovery or memorable event in the history of astronomy will be highlighted. This month, we look at the 100-inch Hooker Telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory.

Each month as part of this new series from the Historical Astronomy Division of the AAS, an important discovery or memorable event in the history of astronomy will be highlighted. This month, we look at the 100-inch Hooker Telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory.

“High in heaven it shone, / Alive with all the thoughts, and hopes, and dreams / Of man's adventurous mind,” says one poet describing first-light of Mount Wilson’s 100-in Hooker Telescope late in the evening of 1 November 1917. The story of this centenarian instrument is really the story of George Ellery Hale’s driving passion to push the boundaries of astronomy and astrophysics with newer, larger instruments.

“High in heaven it shone, / Alive with all the thoughts, and hopes, and dreams / Of man's adventurous mind,” says one poet describing first-light of Mount Wilson’s 100-in Hooker Telescope late in the evening of 1 November 1917. The story of this centenarian instrument is really the story of George Ellery Hale’s driving passion to push the boundaries of astronomy and astrophysics with newer, larger instruments.

Mount Wilson Observatory had a rocky start. The original plans between University of Southern California and Harvard Observatory intended the site to house the world’s largest refractor, the Alvan Clark 40-inch. After an 18-month expedition in 1889-1890, harsh weather and hostile hikers drove the observers from Mount Wilson. Consequently, Hale supervised the installation of the 40-inch telescope at Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin.

In 1903, Hale visited Mount Wilson because the Advisory Committee on Astronomy of the Carnegie Institution of Washington to which he belonged wanted to fund the establishment of a solar observatory. Hale applied to the Institute to fund such a facility at Mount Wilson shortly after returning to Chicago. Confident the endeavor would be funded, he moved his family West in December. Then, in June 1904, he signed a 99-year lease with the Mount Wilson Toll Road Company for 40 acres on the mountaintop. In December 1904, the Institute approved the plans for the Mount Wilson Solar Observatory.

In 1884, Hale’s father had ordered a 60-in diameter disk of plate glass, 7½ inches thick and weighing 1,900 pounds, from the St. Gobain Glassworks of France. Hale intended to transform it into a reflecting telescope, but until then had not had the necessary funds. In Autumn 1905, opticians began figuring and polishing the spherical mirror to the required parabolic shape. As it neared completion, the surface was badly scratched in April 1907. Although the mirror had to be ground back down to a spherical shape, then figured and polished once more, it was completed in September 1907. Until this point, a 4-foot-wide trail traversable only by foot or mule provided access the Observatory. With the new telescope underway, the road was widened to 10 feet in 1907 so they could transport 150 tons of mounting and lens up the mountain. By July 1908, everything was atop Mount Wilson. The telescope saw first-light by December 1908. For the second time in his life, Hale had built the world’s largest astronomical instrument.

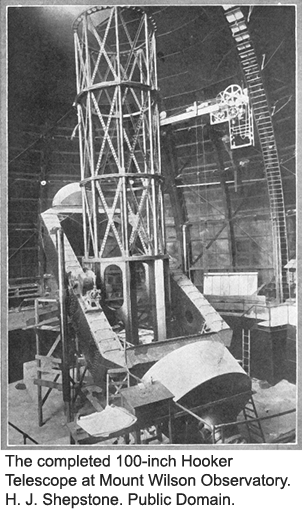

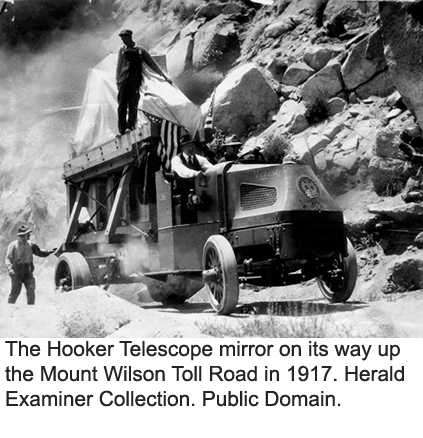

Hale was not about to stop there. While the 60-inch was under construction in 1906, Hale ordered a 4.5-ton disk of glass with a 100-inch diameter from the St. Gobain Glassworks. After several failed attempts, the disk arrived in Pasadena, California, in December 1908. However, numerous imperfections rendered it useless. For the next few years, all further attempts by the company were failures. Additional tests on the original proved it to be acceptable after all, so shaping began in March 1913. Work on the dome was well underway; it arrived at Mount Wilson from Chicago in 1915. The road was widened again to accommodate the mounting, but transportation up the mountain remained dangerous. In July 1917, the mirror was hauled to the top. Thus, Mount Wilson Solar Observatory became Mount Wilson Observatory. That November, a small crowd witnessed first light of the latest, largest telescope in the world. Hale had done it thrice.

Hale was not about to stop there. While the 60-inch was under construction in 1906, Hale ordered a 4.5-ton disk of glass with a 100-inch diameter from the St. Gobain Glassworks. After several failed attempts, the disk arrived in Pasadena, California, in December 1908. However, numerous imperfections rendered it useless. For the next few years, all further attempts by the company were failures. Additional tests on the original proved it to be acceptable after all, so shaping began in March 1913. Work on the dome was well underway; it arrived at Mount Wilson from Chicago in 1915. The road was widened again to accommodate the mounting, but transportation up the mountain remained dangerous. In July 1917, the mirror was hauled to the top. Thus, Mount Wilson Solar Observatory became Mount Wilson Observatory. That November, a small crowd witnessed first light of the latest, largest telescope in the world. Hale had done it thrice.

The 100-inch telescope facilitated the discovery of the existence of other galaxies, measuring their distances and corroborating the theorized expansion of the universe, measuring stellar diameters, and confirming the nature of red supergiant stars. For nearly 100 years, its users have pushed the boundaries of astronomy and astrophysics.

- Babcock, H. 1938 “George Ellery Hale” PASP 50: 295

- Babcock, H. 1939 “In 1903” PASP 51: 299

- Simmons, M. 1983 “The History of Mount Wilson Observatory: Bringing Astronomy to an Isolated Mountaintop,” Mt. Wilson Observatory Association

- Noyes, A. 1922 Watchers of the Sky

- Hirshfeld, A. 2014. Starlight detectives. New York, NY: Bellevue Literary Press.

Each month is an exciting new adventure into the archives of astronomical history, but before I continue any further, I would appreciate your feedback to ensure my writing is reaching the largest audience possible. Please participate in a brief questionnaire (approximately 10 minutes) about the style and content. You may also submit any suggestions for future topics. Thank you!