The AAS Open Access Publishing Model: Open, Transparent, and Fair

Kevin Marvel American Astronomical Society (AAS)

Julie Steffen American Astronomical Society (AAS)

Ethan Vishniac American Astronomical Society (AAS)

As of 2022, all AAS journals are open access. What does our business model look like for the journals now, and why did we choose it? Here AAS Executive Officer Kevin Marvel, Chief Publishing Officer Julie Steffen, and Editor in Chief Ethan Vishniac provide a transparent look at the history and evolution of the journals’ business model, the rationale behind the choices made, and what authors are paying for when they publish in the AAS journals.

The AAS Journals' Business Model: Then

In 2021, the American Astronomical Society (AAS) converted its journals from a “hybrid” business model — which relied on subscription revenue and author charges to cover the costs of operating our journals — to a business model reliant only on author charges. Before this transition, the AAS received roughly 1/3 of its total journal revenues from subscription revenue and 2/3 of its total journal revenues from author charges.1 Note that we also allowed authors to pay an additional Gold Open Access fee about 50% higher to enable the article to be made available fully Open Access immediately. The number of authors taking up this option increased steadily over the years we had it available but never exceeded 20% of our total published content.

The reason for making this significant change to an author-charge-only business model was that the alternative — so-called “transitional agreements” that some publishers have implemented in response to policy pressure from funders and governments forcing a move to Open Access publishing — is inappropriate for AAS journals. These “transitional agreements” would require AAS to undertake individual negotiations with hundreds and hundreds of institutions to establish “read and publish” or “publish and read” arrangements,2 because our authors are widely distributed among many institutions and in many countries. This was fundamentally impossible for the AAS, as the logistical overhead and administrative burden of this kind of model is far greater than simply switching to a fully Open Access business model based on author charges. Other reasons why this model is challenging for AAS are described in Appendix A.

The hybrid business model that we had employed since 20113 utilized a concept of “digital quanta” to fairly charge our authors for the work required to peer review and publish their manuscripts. In this model, authors were charged per “digital quantum,” which refers to a fixed amount of text (350 words), a simple figure, a table, a video, a figure set, and so on. We established rates for each type of content that covered the costs of handling that content. We then tallied up the number of digital quanta in each article at the time of submission, informing our authors what their charge would be, and — barring exceptional additions or subtractions of content (or particularly complicated content) — invoiced the authors for their manuscript just prior to publication based on this original digital quanta tabulation.

This author charge model was fundamentally fair, because the costs we incur as publishers scale linearly with the amount of content contained in an article. Longer papers take more time to handle, to copy edit, to review, and to publish — regardless of whether they are published digitally or electronically. The cost of the paper and printing has not been the major cost-driver in scholarly publishing for decades, unfortunately; many who do not work in publishing still erroneously believe that shifting to digital publication eliminates all costs that are connected to the length and complexity of the manuscript. This view is wrong. Publishing longer, more complex papers costs more because people do the work that takes a manuscript from draft form to a final, published article, and the amount of time they spend on a manuscript scales linearly with length, and at least linearly with complexity.

Multiple figures take more time and effort to process than a single figure, and complicated digital objects like videos or interactive figures can take even more time to incorporate into the final published article. Long, complicated tables take much longer to lay out, copyedit, and provide quality control for than short, simple ones. We also employ data editors who advise authors on how to present data and to curate it optimally in the final published article. In addition, we employ a statistics editor who advises on any relevant statistical matters within an article. These additional advisory improvements to manuscripts have costs as well that increase with the length and complexity of the content in the manuscript; some articles need this extra work, some do not.

Under this business model, when our authors created short, simple articles, they were charged less. When articles were long or complex — or when they contained numerous figures, complicated statistics, lengthy, large, or complex data presentations, or complicated digital objects — they were charged more. This was justified because our own editorial team and our contracted publisher incur costs based on the amount of work that they do, not the number of manuscripts they process.

Our community of authors embraced this model, and during the period we had this charging model in place we saw continued growth in submitted manuscripts, no challenges with authors paying their fees, and an enhanced ability on our part to justify and explain our charging model because this system is fundamentally fair — no author is paying more or less than what they rightfully owe for the services provided. We also maintained a small waiver budget to support authors with no or limited funding to help cover the costs.

The AAS Journals' Business Model: Now

As the policy space has changed, especially in Europe, driven by Plan S and other funding initiatives, we considered how best to continue to fairly serve our author community in an Open Access business model, while preserving at least some of the fairness built into our digital quanta author charge model. We concluded that a three-tiered system that fairly charged articles of three different lengths for the cost of processing them would work best for our community. This would fairly charge longer, more complex manuscripts for the additional work required to process them and give a break to simple, short manuscripts with a lower charge.

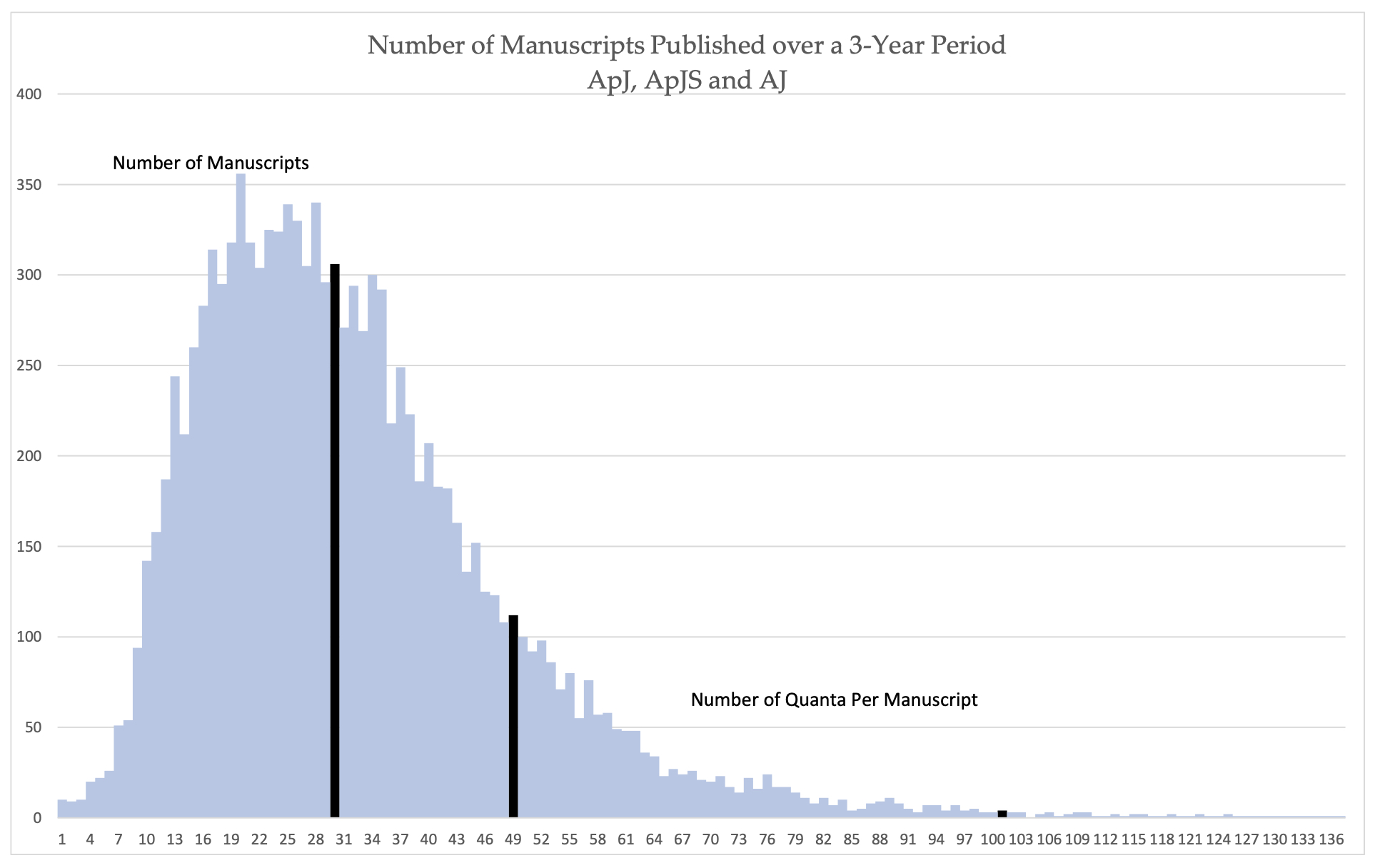

To determine where we should place our tiers, we analyzed three years of manuscripts published in our journals under our digital quanta system. Figure 1 below shows the number of manuscripts that have digital quanta counts of varying lengths. The image is like a “student’s t-distribution,” with a long tail of very long/complex papers (and a fixed cutoff on the shorter end, as there is a limit to how short a manuscript one can write and present a valid scientific result; the very short manuscripts in the distribution are errata, not regular papers), combined with a slightly skewed Gaussian distribution of intermediate length papers.

We then tabulated the total costs incurred for peer reviewing and publishing manuscripts of varying lengths to select the cost for each of the three tiers. After doing so, we sampled several papers from each tier to see what they would have paid under the old model for Gold Open Access vs. their charge under the new model, and we attempted to maximize the cost savings for the author within the tiers. This resulted in the charge structure we have currently for ApJ, ApJS, and AJ of $1,172 / $2,651 / $4,589 for quanta counts of <30 / 31–50 / 51–100 and a long article surcharge of $250 for >100 quanta. ApJL, our rapid-to-press journal, has two tiers close to our middle tier price for our mainline journals. Note that the Planetary Science Journal (impact factor 3.4) was started during our planning for conversion of our other journals, and it was decided to keep it on the digital quanta model for the time being.

We also note here that as we transitioned to Open Access, we expanded our waiver budget to enable access to our journals for authors who may produce excellent science, but who may not have the financial ability to pay the cost of publication. A process exists to receive requests for such waivers and award them, but the waiver process is not meant to pay the difference in tier prices for authors whose institutions are attempting to pick and choose the rate they will opt to pay. Requests of this type will be rejected out of hand going forward.

The Changing Scholarly Publishing Landscape

As it turns out, other journals in our discipline have now embraced the Open Access business model and decided on their own, different, business models. In one journal’s case, a single rate is charged per manuscript (higher than both of our lower tier rates). In another, they have used a “subscribe to open” model, but authors from countries that do not support this journal have to pay page charges. In this model, authors who are from countries that support the “subscribe to open” journal may publish at no cost, but the content is not available to anyone for free until the targeted annual revenue is reached through institutional subscriptions. We view this model as unstainable due to the uncertainty in access it creates as well as the two-tier system for author status — some have to pay nothing, while others pay substantial amounts.

Scholarly publishing is not a simple endeavor, although it may seem so to those who do not operate a publishing enterprise. We live in a challenging time in scholarly publishing, with a strong move to Open Access accelerating each year and old business models being swept away by policy makers attempting to regularize and cheapen the cost of scholarly publishing. It is tempting to apply a single model to all publishers, because it is simpler to do so, but doing so ignores the complexities that each discipline and each publisher encounter, whether they are a for-profit publisher like Elsevier or Springer Nature, or a non-profit publisher like the American Astronomical Society.

The cost growth in scholarly publishing — especially the extremely high subscription rates or package license rates that some publishers have charged — is clearly driven by the for-profit publishers. Having built a dominant position through acquisition and establishment of key titles in multiple disciplines, they are doing what any for-profit activity is meant to do: maximize profit. However, important titles in some disciplines, like the AAS journals, are operated by small, non-profit scholarly societies or organizations. Policies that might work for non-profits may not work or even apply to for-profit publishers and vice versa, making nuanced policy making a requirement. Unfortunately, nuanced policy making is hard work and requires consensus, which can be hard to achieve amidst intensive advocacy efforts with policy makers, led predominantly by those with the funds to support intensive advocacy. And so, we and other scholarly societies are like corks in a stormy ocean, buffeted by waves of policies intended to impact the large publishers, similar to large ships on the ocean.

Because the AAS exists to fairly serve the worldwide community of astronomy researchers, we have established and strongly support our current Open Access model for all the reasons described above. We believe it works for our community and we will defend and explain it with confidence and transparency.

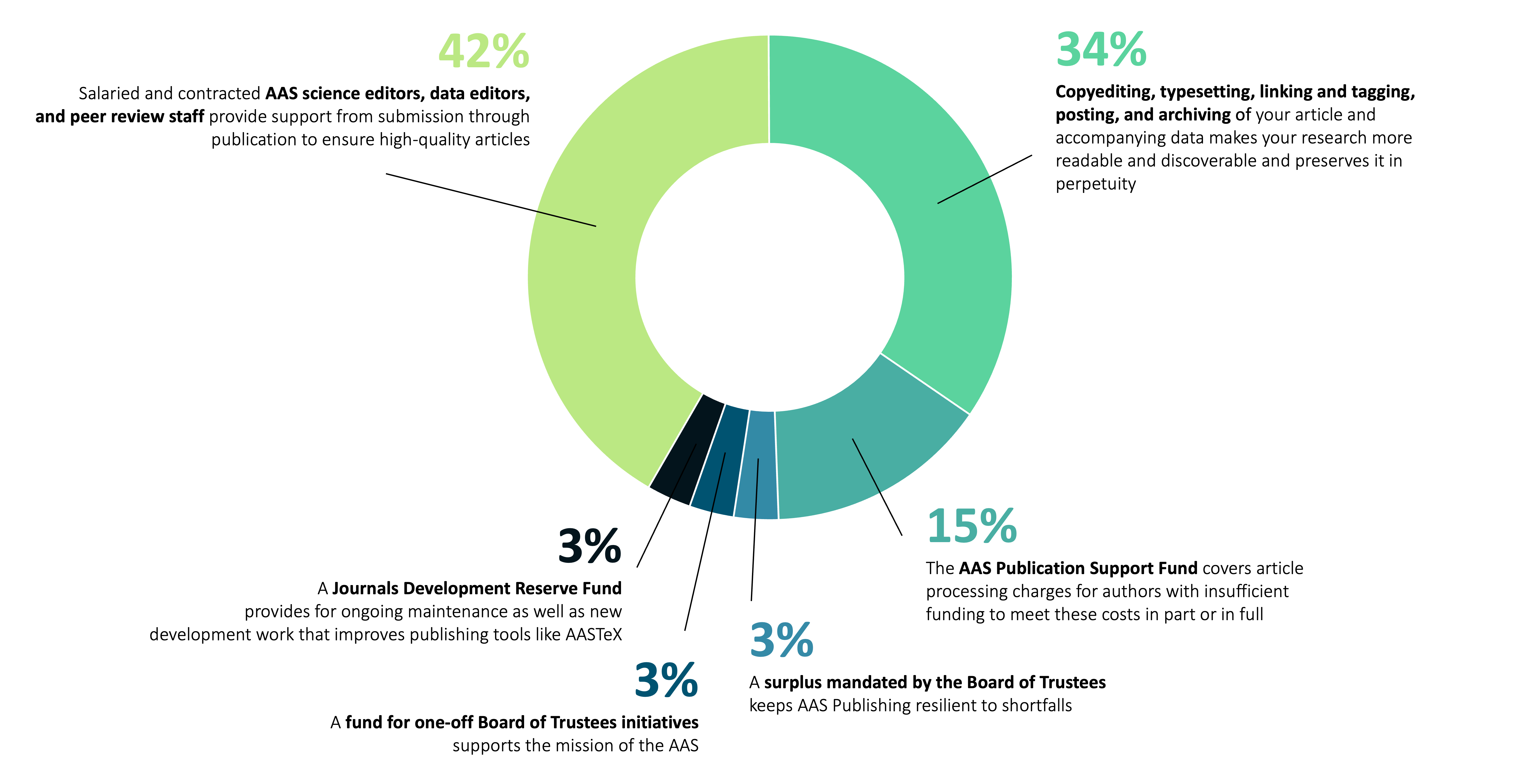

Where Do Author Charges Go?

We also believe that those who provide a service to others may establish a revenue generation philosophy (e.g., a pricing structure) that works for them, is defensible, and that covers the costs required to undertake the work. The AAS has adopted a transparent Open Access business model that fairly recaptures the costs we incur for publishing scholarly works,4 allows us to provide financial subsidy to authors who do not have the means to pay the Open Access fee required for publishing their manuscript, and ensures we continue to operate our journals as a nonprofit venture.

Authors who choose not to publish using our business model, or who work for institutions that choose to ignore or redefine our pricing model, will not be published in AAS journals. This could be devastating to authors, as the AAS’s journals are high impact, provide lasting citation value to authors, and continue a regular practice of innovation and enhancement for our authors’ and community’s benefit. Hopefully, by explaining the history and evolution of our journals’ business model in a fully transparent and open way, as we have in this document, we will eliminate any uncertainty in our model, which will allow authors to enjoy the high-quality service, collaborative peer review, and supportive assistance we provide to improve manuscripts.

Footnotes:

1 Also referred to as “page charges,” “article charges,” “article processing charges,” etc.

2 In this model, institutions are charged a flat fee, which allows their institution free access to the journal content and no charges to their authors for publication. This model fundamentally fails for the AAS, as explained in Appendix A.

3 Before 2011, we charged authors a fee for each published page of content and sold institutional and individual subscriptions.

4 Modern scholarly publishing provides services like professional peer review, copyediting, publishing, archiving, and much more; see https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2018/02/06/focusing-value-102-things-journal-publishers-2018-update

Appendix A: Why do “read and publish” arrangements not work for AAS Journals?

Because the AAS relied on author charges for 2/3 of total journal revenue and only 1/3 for subscriptions before our change to Open Access, our subscription rates were fantastically low — more than 7 times lower than our worthy rival, the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. For roughly $1,800 in 2019, an institution, no matter how many researchers were associated with the institution, would get full access to all our journal content. After a 12-month embargo period, journal content was free to all to read.

“Read and publish” (R&P) and “publish and read” (P&R) arrangements fundamentally cannot work for the AAS Journals given the business model we had before our flip to Open Access.

Imagine an institution with 20 researchers, each of whom publishes two papers per year. Our typical author charges, although they scaled linearly with article length and complexity, were of the order $3,000. This institution would therefore be charged $60,000 a year for author charges and $1,800 a year for a subscription to our content.

Approaching the institution for a R&P arrangement would have us negotiating not with the authors, or their department chair or their college dean, but with the institution’s library, who had been paying $1,800 a year and would now be asked to pay $60,000 + $1,800 = $61,800. Not a very good opening point for a negotiation, but justified, because we operate our journals from a non-profit standpoint. We do not make profits beyond those needed to cover our direct and indirect costs, and our indirect costs are extremely low (10% internally for all revenue-generating activities).

For small institutions, the tradeoff in author charges vs. subscriptions is easier to manage. Imagine an institution with just one author who publishes on average once every other year. In this case it would be an even exchange between subscription fees vs. author charges, but — and this is an important point — the AAS would have to negotiate individual arrangements with hundreds and hundreds of small institutions, some of whom don’t even have an institutional subscription, but do have one author who may occasionally publish with us. Such a model would be unsustainable from an administrative standpoint and add significant costs to the publishing process that are wasteful or would have to be covered via subsidy by larger institutions.

For larger institutions, some with hundreds of authors, the switch to R&P or P&R is even worse than for the mid-size organizations, resulting in annual charges of $100,000 to $250,000 and potentially higher.

Because the bulk of our authors are supported in some way by grant funding at the individual level and the R&P and P&R arrangements will not work effectively for our discipline, we opted to pursue a fair version of an Open Access business model that provides financial subsidies for authors who are without grants or facing financial hardship, and scaled fees that kept the spirit of our “digital quanta” model, but set into tiers that were easier for funders that advocated Open Access to understand and accept.

Our position remains that a single, flat fee for publishing a manuscript is not fair, does not represent how we incur costs for undertaking the publishing process, and is not appropriate for our community.