This Month in Astronomical History: August 2020

Jascin N. Leonardo Finger

Nantucket Maria Mitchell Association

Each month as part of this series from the AAS Historical Astronomy Division (HAD), an important discovery or memorable event in the history of astronomy will be highlighted. This month's guest author, Jascin N. Leonardo Finger, Curator of the Mitchell House, Archives, and Special Collections, writes about astronomer Maria Mitchell. Interested in writing a short (500-word) column? Instructions along with previous history columns are available on the HAD webpage.

Each month as part of this series from the AAS Historical Astronomy Division (HAD), an important discovery or memorable event in the history of astronomy will be highlighted. This month's guest author, Jascin N. Leonardo Finger, Curator of the Mitchell House, Archives, and Special Collections, writes about astronomer Maria Mitchell. Interested in writing a short (500-word) column? Instructions along with previous history columns are available on the HAD webpage.

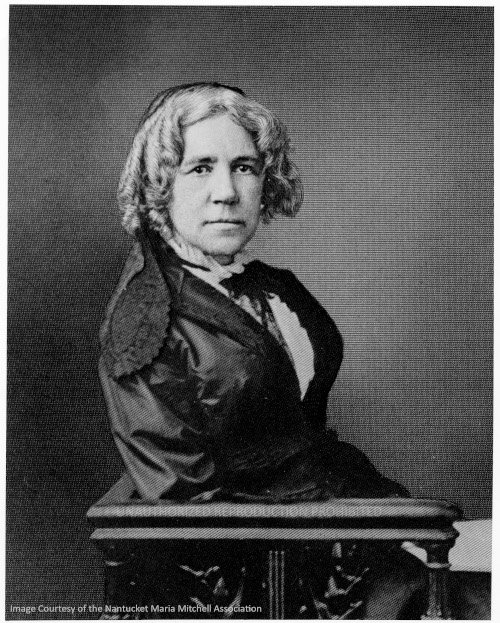

America’s First Woman Astronomer: Maria Mitchell (1818-1889)

Standing under the canopy of the stars, you can scarcely do a petty deed or think a wicked thought. — Maria Mitchell

Born 1 August 1818 on Nantucket Island, 28 miles off the Massachusetts coast, Maria Mitchell took her first breath in a unique and isolated world heavily influenced by the Quaker faith, which supported equality of the sexes. Mitchell was educated equally to her brothers and at a young age followed her father, astronomer and teacher William Mitchell, to the rooftop of their home to observe the night sky. By the age of 12 she clocked the seconds of an annular eclipse while her father observed the event. Her father was Nantucket’s chronometer rater, setting and verifying timepieces for mariners. At 14, while her father was off-island, she rated her first chronometer.

Young Maria was well-known at the Harvard College Observatory, where her father, William, served on the Board of Overseers. Her discovery of a comet on 1 October 1847 convinced many (though not all) that this 29-year-old woman was indeed an astronomer. Even with her discovery and a gold medal from the King of Denmark — the first American and first woman to receive the honor, she still struggled to be accepted in the astronomical community because of her sex.

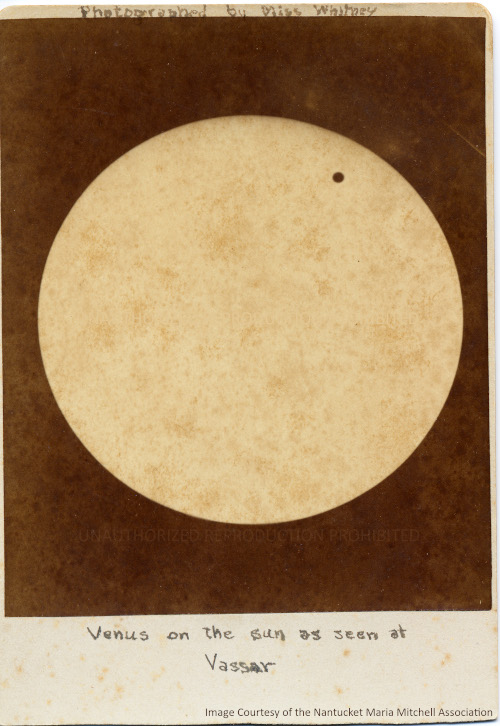

In 1863 the newly formed Vassar Female College invited Maria to serve as professor of astronomy and director of its observatory. There she discovered that many of her students lacked the mathematical knowledge needed to do astronomy, and she found herself unexpectedly teaching remedial math. Mitchell once said, “We are women studying together.” She did not believe in lecturing, but rather in learning by doing. She and her students worked together at the telescopes and on the analysis of observations. She studied sunspots with them, purchasing with her own funds the equipment needed to do so. They took photographs of the transits of Mercury (1878) and Venus (1882). Mitchell provided her students with unique and unheard-of opportunities for women, taking some of them on solar eclipse viewing trips to Iowa in August 1869 and Denver in July 1878. These were the only all-female scientific parties traveling to those events, and her trip to Iowa, funded in part with $100 from the American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac, was thus the only all-female eclipse expedition to receive funding from the US government. To bolster their aspirations, Mitchell would routinely share with her students letters written to her from other astronomers and scientists around the world. Yet even at Vassar, where she taught until 1888, Mitchell’s time was marked by struggles for equal pay.

Mitchell was a trailblazer in many of her accomplishments: America’s first woman astronomer, first woman inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, one of the first women to work for the US federal government, and one of the first women inducted into the American Association for the Advancement of Science. She was a founder of the Association for the Advancement of Women, serving as president for a term, and the founder and chair of its science committee. She was also a founding member of the women’s professional club Sorosis.

Mitchell had a lasting, multigenerational influence on women in astronomy, science, education, and women’s rights. Mitchell’s student Mary Whitney succeeded her at Vassar and became the first president of the Nantucket Maria Mitchell Association (MMA). Another student, Antonia Maury, was a pioneer in spectroscopy, being the first to calculate the orbits of the spectroscopic binaries ζ Ursae Majoris (Mizar A) and β Aurigae. Margaretta Palmer, once served as Mitchell’s assistant in the first year after her graduation, was subsequently hired by Yale University Observatory as an assistant. Palmer was among the first group of women admitted to Yale for graduate school. Credited as the inventor of home economics and euthenics, Ellen Swallow Richards credited Maria Mitchell as a major influence in her life. Richards entered Vassar in 1868 and found her calling in chemistry, completing a bachelor’s degree and then a master of arts in chemistry at Vassar before entering MIT to earn a BS in chemistry in 1873.

Maria Mitchell’s legacy continues today. The MMA — founded in 1902 to protect and preserve her birthplace and legacy — boasts two observatories, a natural science museum, a harborside aquarium, a research center, and her birthplace. World-renowned research in astronomy and other natural sciences is ongoing, as are programs and classes for adults and children. The museums and observatory sites welcome more than 14,000 participants each year. An award-winning internship program, including a National Science Foundation–sponsored Research Experiences for Undergraduates program in astronomy, perpetuate her legacy of learning by doing.

More details on the MMA can be found on its website.

Further Reading

- Albers, Henry. 2001, Maria Mitchell: A Life in Journals and Letters. Clinton Corners, New York: College Avenue Press.

- Booker, Margaret Moore. 2007, Among the Stars: The Life of Maria Mitchell. Nantucket: Mill Hill Press.

- Kendall, Phebe Mitchell. 1896, Maria Mitchell: Life, Letters, and Journals. Boston: Lee and Shepard Publishers.

About the Author

Jascin N. Leonardo Finger is the Nantucket Maria Mitchell Association’s Deputy Director and the Curator of the Mitchell House, Archives, and Special Collections. She has worked for the MMA for more than 30 years.