President's Column

David Helfand Columbia University

At 1:32AM Eastern time on 6 August, the Mars Science Laboratory and its charmingly named rover, Curiosity, executed a perfect landing in Gale Crater. President Obama called the highly complex landing procedure “an unprecedented feat of technology that will stand as a point of pride far into the future.” While we certainly hope Curiosity’s lifetime on Mars is a long one, we must all continue to make the case that we do not want to see this success as the only “point of pride” generated by a solar system mission in the coming decade. And we must make this case in very trying circumstances.

By the time you are reading this column, the NSF Portfolio Review results will have been made public. While I write this in complete ignorance of what those results will be, I am confident that the fiscal reality it portrays, and the hard decisions these realities enforce, will not make all astronomers happy. Looking beyond these immediate concerns, however, the future looks considerably grimmer. It is not a matter of priorities within NSF AST, or within MPS, or within NSF or NASA as a whole. It is the fiscal reality of the nation.

I am not talking about the much ballyhooed “fiscal cliff” that Congress is facing in its lame duck session; I suspect some short-term fix will be found for the debt ceiling limit, tax cut extensions and sequestration. Rather, I am speaking of the decade after decade shift in government spending from investment in the future -- where science holds pride of place -- to transfer payments commonly known as entitlements.

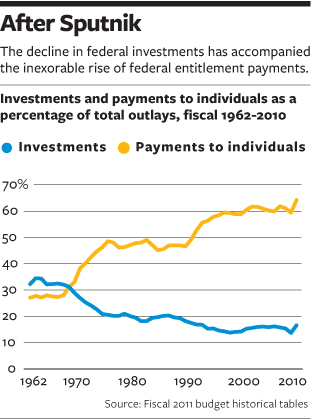

The shift in the balance between these two fundamental roles of government over the past 50 years is frightening. Representative Frank Wolf (R-Va), Chair of the House Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies (CJS -- the committee that oversees the funding of both NASA and NSF) has produced several documents that highlight this evo(devo?)lution in federal spending. Figure 1 shows how the ratio of investments to entitlements has changed from 1.15 to 0.27 over the past 50 years. This is not a graph that describes a society focused on the future.

And there is no comfort in the fact that the federal budget has grown a lot in the past fifty years (both in absolute terms and in terms of its fraction of GDP); entitlements are growing much faster. In a 28 March speech on the House floor, Representative Wolf quoted the conclusion of the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office “[under laws currently in place] every penny of the federal budget will go to interest on the debt and entitlement spending by 2025.” Every penny. That leaves $0 for defense, $0 for education, and, most certainly, $0 for scientific research.

When AAS President Elmegreen testified in March before the House CJS subcommittee, Chairman Wolf had no criticisms of our astronomical priorities or our facilities management -- he just wanted to know why we were not up in arms and doing something about entitlements and corporate tax breaks. The obvious answer is that it is the job of his colleagues to fix those problems, but I think he has a point -- because those colleagues report to us.

In April, I participated in Congressional Visiting Day, an event coordinated by the AAAS and involving the participation of several hundred members of various scientific societies who descend on Capitol Hill to make the case for the nation's investment in scientific research. Under the expert coordination of our John Bahcall Science Policy Fellow Dr. Bethany Johns, fourteen AAS members made dozens of visits to Congressional offices. Using the Decadal Surveys as the blueprint for our priorities, we engaged staff members in lively conversations about the importance of astronomical research in the context of the larger STEM agenda. We were well-received in the vast majority of offices, and it is clear that our science -- and science in general -- enjoys widespread interest.

Indeed, science is one of the few remaining issues garnering bipartisan support. However, when I suggested in several Congressional offices that science was doomed unless the entitlement issue was addressed (and I was careful to avoid advocacy of a particular approach: increased taxes, decreased spending, or, what every bipartisan commission has recommended, a combination of the two), the reception suddenly changed. In one office, traditionally very supportive of the scientific enterprise, I was told that even raising that issue would greatly surprise and disturb some of our most loyal allies.

That is profoundly troubling. To me, it is akin to the attitude of climate change deniers. The issues surrounding a response to climate change -- social, political, and economic -- are vexed, and reasonable people can reasonably advocate different paths. Detailed predictions of climate change consequences are uncertain. But to deny that we are on track to double the pre-industrial atmospheric concentration of CO2 on roughly the same timescale that the federal discretionary budget goes to zero represents a disconnect from reality. Ignoring the federal budget's trajectory is, likewise, untenable. Congressman Wolf is right: whether in the interest of the country, or the narrower self-interest of support for future research, we all need to express our outrage at this looming fiscal catastrophe.

We are still making remarkable progress in our field. Since my last column, the NuSTAR mission successfully deployed its 10-meter-long mast which allows it to focus X-rays in the 8-80 keV band to sub-arcminute precision. This provides, for the first time, human-vision-level resolution in this hard-X-ray band, allowing us, as PI Fiona Harrison said in a recent NPR story on the mission, to “use these new glasses to read the secrets of black holes.” And, the National Science Board has just approved the number one ground-based priority from the 2010 Decadal Survey, LSST. This allows that exciting project to proceed to the final design stage and directs the NSF to include construction costs in future budget requests.

Yes, we continue to live in a golden age of astronomical discovery. The length of that age in the US, however, will depend not only on our effectiveness at selling Congress and the public on how exciting and compelling the questions we pose really are, but on an escape from the fiscal nightmare toward which we are careering. There is no reason we cannot be astronomers and citizens at the same time. Unless a fundamental restructuring of the federal budget occurs, it is difficult to see a bright future for research and discovery.