Improving the Status of Women in Physics (and Astronomy) Departments

Edmund Bertschinger Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Women are now more than 1/3 of physics majors at several top universities and 28% of astronomy assistant professors were women in 20061. Long gone are the days when women were barred from faculty positions in science departments and were not permitted to observe at some astronomical observatories2. Yet women still face challenges that men do not, and this limits the success of the academic research enterprise. Some readers may challenge this premise and I invite them to learn about this topic by attending a Women in Physics or Women in Astronomy meeting. Other readers may be curious about how to improve their departments. This article offers suggestions based on my experience serving for five years as MIT Physics Department Head as well as my service on the Committee on the Status of Women in Astronomy.

The most important lesson I have learned is that committed leadership matters. Leaders are the stewards of institutional culture3. The tone set by a leader permeates an organization. A dismissive leader makes it very difficult to change a poor workplace environment. Conversely, a leader who consistently shows respect and gives encouragement enables a virtuous cycle of increased satisfaction and accomplishment. Sometimes the respect is merely an acknowledgement that inequities are present in lab space, salary, institutional awards or service roles, followed by a commitment to right the wrong4.

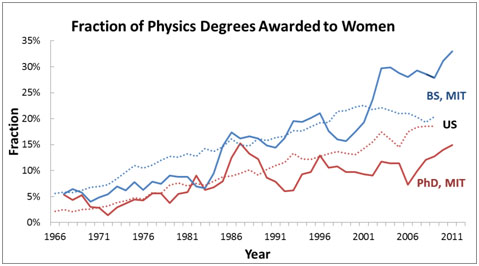

Figure 1: Undergraduate (blue, upper pair) and PhD (red, lower) physics degree statistics from MIT (solid, computed with a three-year boxcar average) and US national averages (dotted). Data from the American Physical Society, IPEDS Completion Survey, and MIT Office of Institutional Research.

These effects are apparent even at the level of individual departments. I compiled the fraction of physics degrees (undergraduate and graduate) awarded to women at MIT over several decades, and compared with nationwide totals (Figure 1). Several notable increases and decreases accompany leadership changes. Curricular changes also matter, especially at the undergraduate level5. For example, after the introduction of a flexible degree option in 2000, physics enrollments more than doubled, with the greatest increases occurring for women. This analysis extends earlier work done by then-undergraduate Laura Lopez6. The variation of female fraction across departments is large. Several other institutions have achieved similar successes (e.g. Florida International, UTEP, Yale) which also appear to correlate with leadership and curricular reform7. You and your students may find such a study similarly illuminating.

Why do numbers matter? While it is difficult to quantify a subjective sense of climate8, there is no doubt that the atmosphere is very different in my department now that women make up 1/3 of our undergraduate physics students. The department culture is collaborative and supportive. Students thrive. I believe that all faculty members acknowledge the change is positive.

The fraction of women decreases at the graduate level and, in some fields, decreases further at the postdoctoral and faculty levels. Why? Is this a bad thing? If so, what can be done about it?

Six years ago I met with our Graduate Women in Physics group and sought their advice about these issues. I was profoundly affected by this meeting. First, the students gave me the confidence that I could make a difference. Second, they told me what I had to do: create a culture of caring.

Their advice resonated with me. More than 25 years ago I had suffered Imposter Syndrome upon starting my faculty appointment9. Junior faculty coming to the end of their appointments told me the competition was fierce and I should expect to fail. As a survivor, I was determined to change the culture around me. I began with mentoring and gradually expanded the circle of respect and encouragement while consistently pushing for excellence. The graduate women empowered me to apply this prescription to the entire department.

I am sometimes asked what one thing I have done to increase diversity and to improve the climate in my department. It is to show respect. Respect others by listening to them, especially those whose voices have not been heard. Respect them by addressing their concerns. Show respect by learning best practices10. If you try instead to produce or work from a checklist, you are on the wrong course. There is no substitute for caring leadership.

Some will object that difficult people prevent establishment of such a culture of caring. One grumpy, misogynistic tenured faculty member can cause many difficulties, but he cannot prevent change. Committed leadership is essential in handling such cases. Even such faculty members generally respond favorably to respect wrapped around clear standards of behavior. Department chairs have sticks as well as carrots to offer. If the department chair is unable to handle such problems effectively, a dean or higher officer can. But I believe most cases are best handled at the department level. Department chairs need training in personnel management which can be acquired at their university or from other professionals11. The Committee on the Status of Women in Astronomy can be a resource12.

Whether or not you are a department leader, you will be more effective by identifying allies at your university and across your profession. The importance of collaboration is growing in physics and astronomy because it enables research that cannot be accomplished by individuals. The same is true in fostering diversity and inclusion. Allies also provide advice and mentoring. For me, they provide positive energy and support which is important for sustaining effective leadership.

You may be surprised who your best allies will be. I have found staff members from all across the university to be the most committed volunteers eager and able to help foster a culture of caring. Whether they are administrators, administrative assistants, or service workers, staff members thrive and contribute best when shown respect and treated as allies. They can do wondrous things, such as organize a major university event as volunteers which stimulates a year-long discussion of diversity and excellence. This is what happened recently at MIT13.

When it comes to addressing gender inequity, men can be effective allies14. We all harbor implicit bias, and people who violate gender stereotypes attract notice. While I am uncomfortable with the inequity of being taken more seriously by male colleagues because of my gender15, I care about results. I have repeatedly used my gender to advance discussions of women in science and engineering16.

Implicit bias remains an important problem limiting the numbers and success of women in physics and astronomy. I am continually astonished that some scientists doubt its existence. I wish every such person could have the experience of a male undergraduate who attended the 2011 Conference for Undergraduate Women in Physics at MIT. This student attended on a dare from a female classmate who also attended the conference. He began paying attention when a very successful senior physicist spoke about her career path. At one point, the senior physicist described a meeting of about 30 women in physics that her husband had attended with her. The husband, also a physicist and a faculty member, recounted that his first reaction had been to run out of the room. However, his next thought was “this is what it is like for you every day.”

The undergraduate male listening to the woman’s experience was speechless. Later that day he was still reeling from the new perspective given him by the lecture and his experience at a conference being vastly outnumbered by women. He committed to sharing his insight with fellow students. That day, implicit bias was revealed and an ally was made.

It is not easy to convince senior faculty members that they may be biased, despite decades of research showing such bias in others17. Sometimes, direct experience of the Implicit Associate Test18 can help. However, in matters of recruitment, it is unsafe to neglect implicit bias. That is why many universities require search committee training19 and affirmative action review. To be most effective, responsibility for this training should be taken by the department chair or dean.

If you are not the department chair, what can you do to improve the status of women in your department? You can start by finding allies among staff, students, postdocs, and faculty. Invite the department chair to lunch. Share with him or her what you feel works well in the department, then give one or two examples of problem areas where the chair can make a difference. I like the strategies recommended by John Kotter in his book Leading Change. Help the chair achieve some small early successes before asking for more challenging remedies. If progress stalls, ask the chair (if Physics) to consider inviting a Climate Site Visit review to be conducted by the Committee on the Status of Women in Physics20.

In the end, we all want our departments to be the best they can, which can happen only when all of the members thrive. In my experience, people do their best when a culture of caring and respect is established. It may take a decade or more for the culture to complete this transformation. Sustaining it requires continued care and attention. When the tools of cultural transformation are learned in graduate school, we will be on our way to full equity.

________________________________________

1American Institute of Physics Statistical Research Center; http://www.aip.org/statistics/

2http://www.aip.org/history/cosmology/ideas/women.htm

3E. H. Schein, Organizational Culture and Leadership, San Francisco: Wiley & Sons (2010)

4A Study on the Status of Women Faculty in Science at MIT, 1999; http://web.mit.edu/fnl/women/women.html

5B. L. Whitten, S. R. Foster, & M. L. Duncombe, What Works for Undergraduate Women in Physics? Physics Today, 56, 46 (September, 2003); http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.1620834

6L. A. Lopez, poster presented at the Women in Astronomy II Conference (Pasadena, 2003); http://www.aas.org/cswa/MEETING/lopez1.pdf

7V. Incera, Making Cinderella Shine Without Magic, APS Gazette, vol 31., no. 2, 1 (Fall 2012); http://www.aps.org/programs/women/reports/gazette/upload/GAZ-fall2012.pdf; L. Kramer, E. Brewe, & G. O’Brien, Improving Physics Education through a Diverse Research and Learning Community at Florida International University, APS Forum on Education Newsletter, Summer 2008; http://www.aps.org/units/fed/newsletters/summer2008/kramer.cfm

8Sociological research suggests that about 25% is required, e.g. M. E. Heilman, Organiz. Behav. Hum. Perf. 26, 386 (1980); http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(80)90074-4

9http://womeninastronomy.blogspot.com/2011/12/impostors-welcome.html

10E.g., Gender Equity report, American Physical Society; http://www.aps.org/programs/women/workshops/gender-equity/upload/genderequity.pdf

11E.g., http://www.departmentchairs.org/online-training.aspx

12http://www.aas.org/cswa/diversity.html#howtoincrease

13Institute Diversity Summit 2012; http://diversity.mit.edu/sites/default/files/institute_diversity_2012.pdf

14N. Hopkins, Diversification of a University Faculty: Observations on Hiring Women Faculty in the Schools of Science and Engineering at MIT, MIT Faculty Newsletter, vol. 18, no. 4 (March/April 2006); see also the January, 2011 CSWA Town Hall What Can Men Do to Help Women Succeed in Astronomy? http://www.aas.org/cswa/Jan11/townhall.html

15B. A. Barres, Does gender matter? Nature 442, 133 (2006); http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/442133a

16E. Bertschinger, Leaders in Science and Engineering: The Women of MIT, STATUS, American Astronomical Society, June/July 2011, 11 (2011)

17C. A. Moss-Racusin, J. F. Dovidio, V. L. Brescoll, M. J. Graham, & J. Handelsman, Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 16474 (2012) ; http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1211286109

18Project Implicit, http://implicit.harvard.edu/

19ADVANCE Program for Faculty Searches and Hiring, U. Michigan; http://www.advance.rackham.umich.edu/handbook.pdf

20APS Climate for Women Site Visits, http://www.aps.org/programs/women/sitevisits/index.cfm